Amritsar was born in Lahore. It was born inside the walled city, in a small house, in its narrow winding streets. It was the month of Assu, a month that corresponds with the months of September and October in the Gregorian calendar. It was a month when the monsoon rains, having unleashed their fury had finally taken mercy and receded. The demons of the summer had been defeated, while the tyrant winter was still imprisoned. It was the time of the year of perfect harmony, when nights were balanced by the day, the heat by the cold. It was the time of the year so uncharacteristic of the extremities of Punjab that it seemed out of sync, an anomaly, to its vagaries.

Amritsar was born in the family of Sodhi Khatri, a family of ancient kings, a family that was destined to rule, not just the kingdom of this world, but also the higher realm, miri and piri, as it is articulated by the sixth Sikh Guru, Guru Hargobind. They were not destined to be ordinary rulers, but true rulers, Sacha Padshah, whose reign even overshadowed the reign of the mighty Mughal Empire. This new kingdom that was their destiny was born along with Amritsar, in Lahore, in the year 1534.

Amritsar lived in Lahore, till it was seven years old, till the time that its parents, Hari Das and Mata Daya were alive. They died in the same year, leaving their child, orphaned. The child, initially named Jetha was raised by his grandmother, in a small village, near present-day Amritsar, where the child first interacted with Guru Amar Das, the third Sikh Guru, and became his lifelong devotee. Bhai Jetha, eventually became part of the Guru’s family, marrying his daughter, Bibi Bhani. Such was his devotion to the Guru that he was chosen his successor. Bhai Jetha became Guru Ram Das, the founder of Ramdaspur, the name by which Amritsar was once known.

Inside the walled city of Lahore, in an area known as Chuna Mandi, close to the Kashmiri Gate, there is a gurdwara that marks the spot where Guru Ram Das was born. It was lying in shambles till a few years ago, much like several other gurdwaras across the country before it was renovated and opened for Sikh pilgrims, as part of the series of gurdwaras that have been revamped by the Pakistani state.

Lahore was born in Amritsar. Actually, about eleven kilometers west of the city. It was born as a twin child, its fate permanently sealed with the city of Kasur that was born along with it. It is, however, not possible to pinpoint the exact day, the season or even the year of Lahore’s birth. It first came to existence at a time, when time did not exist. There was no history or chronology, but the circular trajectory of mythology. This wasn’t a time of people, but rather of characters, caricatures, and archetypes. This was the time of the perfect man, the just king, his perfectly devoted wife, and his perfectly loyal brother. This was the time of the greatest villain, a character, so powerful that it was as strong as the power of ten. This was a time when gods and demons lived as men and women, a time when there was either good or evil, nothing in the middle.

It was at that time, when history was yet to be conceived that, Lahore was born in the ashram of Bhagwan Valmiki. The greatest sage of his time, for that was a time when nothing existed in ordinariness, Bhagwan Valmiki was composing the greatest book ever, when the cries of Lahore and Kasur first resonated in the ashram. It was the story of their father, of Lord Ram that Bhagwan Valmiki, the Adi Kavi, the first poet, was composing when he heard these cries. Sita, their mother, had found refuge in this ashram, when she had been banished from Ayodhya, after her return from Ravana’s Lanka. It was her story, of her marriage with Ram, of her exile from Ayodhya, of her capture by Ravana, of her rescue by Ram and her trial in Ayodhya that the Adi Kavi had decided to write about, in the process composing the first verses of poetry humans had ever realized. Lahore was born along with the Ramayana.

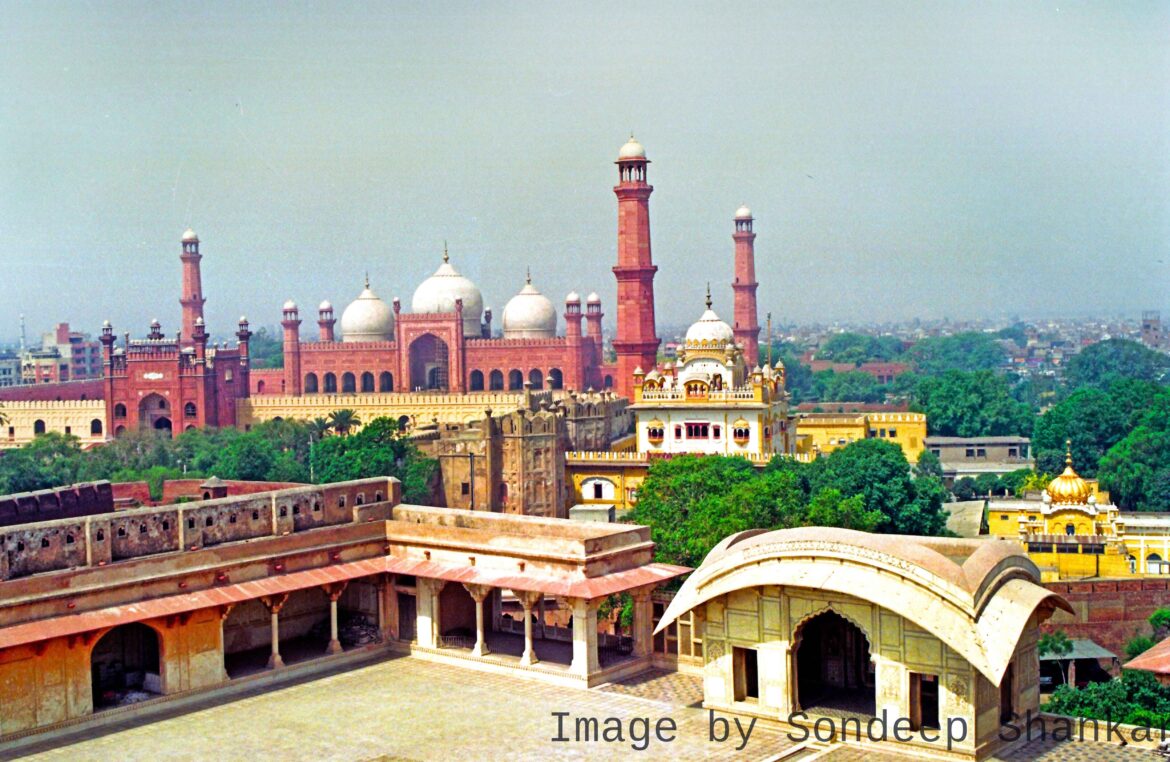

Her twin sons were named Lava and Kusha. Lava founded the city of Lavapur, the city of Lahore as it came to be known, while Kusha founded Kasur. Today, about eleven odd kilometers from Amritsar, Bhagwan Valmiki Tirath Sthal, marks the spot where the ashram was located and Lava and Kusha were born. The three cities, at their birth, were tied together in a triangle, a relation that is now testified by their cartography. In contemporary Lahore, at that highest point of the city, next to the river, where the first signs of civilization developed, where lie the earliest traces of Lavapur, there is a small temple dedicated to the founder of the city. Inside the Lahore Fort, next to the Alamgiri Gate, are the remains of the temple of Lava.

*

How is one to imagine the cities of Lahore and Amritsar, whose origins are so deeply intertwined with each other, separated today, by boundaries that doesn’t just divide geographies and people, but also mythologies, legends, religions, cultures, heroes and villains? It is a border that lies in the middle of these two cities, fabling stories about itself, about its previous incarnations in different forms, telling tales about its inevitability, its naturalness. Chanting mysterious mantras, the border blows in the direction of these cities, transforming their appearances through its prayers.

Lahore today is the ultimate symbol of Pakistani nationalism – a Muslim majority city, the site of the Lahore Resolution, where the Muslim League first demanded a separate homeland for the Muslims, home to Minar-e-Pakistan and host to the proud Mughal architecture, the Lahore Fort, Badshahi Masjid, a tradition that marks the zenith of Muslim civilization in an undivided subcontinent. Besides a few, inconvenient, remnants of traditions scattered sparsely around the city, all those traces of a pre-Pakistan Lahore have been suffocated and left to die. It is easy, in fact encouraged, to forget about that lost city, that lost geography which connected Lahore with Amritsar and Delhi, a Lahore that emerged as an important economic, political and cultural hub, because of its strategic location on that ancient route that flowed from Bengal to Kabul, a river dammed up by the border.

Lahore today is still an important city, perhaps even more important than it has ever been, but it is not the Lahore of the past. Its contemporary geography and location is an awkward testimony to its changed status. A city that once looked in both directions, has today its back towards the east, and looks desperately towards the west, towards Islamabad, Kabul and beyond, in search of a new identity, in search of a new incarnation.

The story of Amritsar is not much different. It was wedded to Lahore at its birth, tied a knot with the hem of the city that spanned over several centuries. It was a marriage that was sanctified by Valmiki as Ramayana his witness, by the shabd of the Gurus, and the blessings of Sufi saints, like Mian Mir. It was a marriage of interdependence, of convenience and even complimentary traits. It was a marriage in which Lahore took on certain roles, and Amritsar others. Thus in 1799, when a young Ranjit Singh took over Lahore, he effectively became the ruler of Punjab, with Lahore the political symbol in his control. But, without the blessings of Amritsar, the spiritual symbol, he could not yet call himself Maharaja, the capture of one, incomplete without control over the other. Lahore held the past, while Amritsar was the future. Lahore was regale, while Amritsar sacred. If Lahore was miri then Amritsar was piri. The two were not two distinct entities, but one. They were an extension of each other, incomplete without the other. Like an archetypical marriage, they were two bodies and one soul.

The divorce was sudden, as abrupt, as the gradual dependence that had developed over (almost) four hundred years of marriage. It was an immediate severing of all relationship, a violent rupture of all connections. Memories of Lahore, however, continue to haunt Amritsar. It is a relationship the city today searches for, sometimes with Delhi and at other times with Chandigarh. It is that primary relationship that impacts all of its subsequent relationships. The memory of the divorce lurks within its subconscious, hampering it from fully realizing itself, from fully expressing itself.

*

The road leads nowhere, meandering on non-committedly. Its not meant to be traveled on, to be explored. It is not meant to connect one part with another. It is meant to provide a semblance of connectivity, meant to fill up vast space of empty tracts of land. It is aimless, pointless, stranded, like a branch of a family tree that has no progeny, that has no purpose.

One after another, villages and hamlets, emerge on both sides of the road. They are the children of distantly related family members with no children of their own. They are no longer part of the immediate family, no longer invited to its events. They are confined within their own circles, isolated in their periphery from the economic structures of the core. Their names represent their marginalized positions – Dera Chahal, Jhaman, Hair and Bedian, terms that have no resonance in contemporary Lahore, the Lahore of Islampura, Rehman Park, Model Town and Defence (DHA), a Lahore of postcolonial sensibilities, tinged with the flavor of Islamic nationalism.

I am traveling on the Bedian road, a road named after the village Bedian, which in turn was named after the Bedi descendants of Guru Nanak who were allotted land in this village. It is only the name that survives, a name that once resonated with significance, a name that today represents nothing but outskirts of Lahore, of vast agricultural fields, the downtrodden villages, a dilapidated road, and a few luxury farmhouses. Beyond these is the border, casting its spell, chanting its mantra. The road collides with the wizard and dies unceremoniously. It is a battle that it is destined to lose.

The road once connected Lahore with Amritsar, one of the many that connected these two cities. Here the peripheries of the two centers, interacted, creating villages and hamlets through this intercourse, these villages and hamlets bearing children of that relationship. Standing on a vacant ground, facing the historical village of Hair, now reduced to poverty and insignificance, are the remains of this unwanted child, the remains of a shrine that was constructed here by Prithi Chand, the eldest son of Guru Ram Das, a shrine that was intended to rival Harminder Sahib, at Ramdaspur. It is a worn-down structure, stripped off all its ornaments, the paints, the frescoes. Its sacred pool, created as an alternative to the pool of Amritsar, is now lost, completely covered, its broken bricks scattered all over this ground.

The present condition of the structure however, is misleading. For a brief period, the shrine, named Dukh Nivaran, was important. For a brief period it attracted several Sikh pilgrims, who believed Prithi Chand’s lies that he was the rightful spiritual successor of his father that he was the fifth Sikh Guru and not his younger brother. In this endeavor, he was supported by many – Mughal officials and corrupt Masand, Sikh deputies appointed by Guru Ram Das, as his representatives, in different parts of Punjab. The strategic location of the village of Hair, made it easier for Prithi Chand and his followers to intercept Sikh devotees, on their way to meet the Guru, and to expand their network. With the Sikh pilgrims also came their offerings. The exchequer of Prithi Chand swelled, while that of Guru Arjan, dwindled, who was at that time in Ramdaspur. For that brief moment, it was Hair and this shrine that began to overshadow Harminder Sahib.

After Prithi Chand’s death his smadh was constructed at Hair, while his movement was continued by his son, Meherban. This movement in Sikh history is referred to as Minas, the scoundrels. It was one of the most potent challenge to all the subsequent Gurus, after Guru Arjan. After the formation of the Khalsa, they were referred to as Panj Mel – one of the five dissenting groups with whom the Khalsa were forbidden to engage. The Minas finally lost this battle for legitimacy, the struggle for spiritual inheritance of the Gurus in the 19th century, when they split into several parts and got incorporated into the formal Sikh community. With the disintegration of the community, the village of Hair too lost its political importance, as the memory of Prithi Chand, of the Minas and Dukh Nivaran began to disintegrate and crumble.

*

Before there was Partition, before there were riots and mass exodus. Before there was religious nationalism, the division of Punjabis into multiple airtight traditions. Before there were contemporary incarnations of Mughal armies and the Guru’s forces, fighting a perennial battle, correcting historical injustices. Before Lahore became a Muslim city, the city of Sufi saints, and Amritsar, the city of Gurus, there was Mian Mir and Guru Arjan.

Their friendship first began, at the same house in Chuna Mandi, where Guru Ram Das was born. Here a young Mian Mir, years away from becoming the Sufi saint that he did, would attend the religio-philosophical discourse of Guru Ram Das, whenever the Guru came to Lahore, from Ramdaspur. This was a time before the communalization of identities, the partitioning of religious traditions, a time when it was the norm, and not an exception, to have Hindu, Sikh and Muslim devotees of the Guru. It was at these gatherings that a young Mian Mir, met the young future Guru. They formed a connection that was to become representative of the symbiotic relationship between Sikhism and Islam.

Upon becoming the Guru, despite the opposition of his elder brother, Guru Arjan continued the construction work at Ramdaspur, whose foundation had been laid by his father. He began the construction of Harminder Sahib, the future Golden Temple, which was in time, to become the most important Sikh gurdwara anywhere in the world. Before however construction began for Harminder Sahib, a message and a delegation traveled from Ramdaspur for Lahore (according to oral narratives of the descendants of Mian Mir, residing in Lahore), sent by Guru Arjan, to bring his friend Mian Mir to the city, to lay the first brick of the foundation of what was to become the identity of the city. Mian Mir, traveled in a palanquin, sent by the Guru and laid the foundation of Harminder Sahib, tying together the cities of Lahore and Amritsar in a lifelong relation.

Years later, when on the orders of Emperor Jahangir, Guru Arjan was being tortured in Lahore, on the banks of Ravi, before his execution, Mian Mir reached out to him, and asked for his permission to destroy the city of Lahore, to stop this torture. He was willing to sacrifice his home, to sacrifice the entire city, for his love of the Guru, but the Guru refrained him from doing so. After Guru Arjan’s execution, Mian Mir maintained a cordial relationship with his son, the sixth Sikh Guru, Guru Hargobind. It is a relationship that continues to be remembered and celebrated by certain groups and communities.

*

I met Bhai Ghulam Muhammad at his home, in Lahore, in February 2014. He passed away in April. His home was located close to Data Darbar, shrine of the patron saint of the city. A thousand years old, the shrine is as old as the known history of Lahore. Its existence and continued significance, represents a continuation of a cultural and spiritual life of the city.

Residents of Lahore, take much pride in the city’s historicity, its recent and ancient past. But, is Lahore, in its contemporary incarnation, the same city that it was, that it has been for a thousand years? Lahore was never Bhai Ghulam Hussain’s city. His home was Amritsar. But the city changed in 1947. Just like Ghulam Muhammad’s family, the city too migrated to Lahore, leaving in its shadow, a distant memory, of what the city once had been. The city, where Ghulam Muhammad was traveling to, was also not Lahore anymore, the glorious pride of Punjab, the multicultural jewel of the crown, of undivided British India. This was a new Lahore, a new city which only shared its name with that glorious past.

Bhai Ghulam Muhammad came from the family of Bhai Sadha and Madha, the Muslim rubabis appointed by Guru Tegh Bahadur to perform kirtan at the Harminder Sahib. The performance of kirtan at Sikh gurdwaras by Muslim rubabis was a tradition that started with Bhai Mardana and Guru Nanak, maintained by the subsequent Sikh Gurus. His was one of the most respected family of the city of Amritsar, the family that formed a connection between the Guru’s shabd and thousands of their devotees. His family, one example, out of several that highlighted the complex, complicated relationship between different religious communities and hybrid identities. “We knew the Granth by heart…nothing about being Muslim,” he told me.

Once guardians of the Gurus’ words, they were reduced to odd jobs in Lahore. Only recently with a growing interest in Sikh heritage in Pakistan, the family began performing kirtan again, however this rediscovery of the profession, a far cry from what the situation had been prior to Partition. The odd jobs continued. In 2008, Bhai Ghulam Muhammad was barred from performing kirtan at Harminder Sahib, for he was not an Amritdhari Sikh. His family had performed kirtan for generations at the Harminder Sahib, without ever being Amritdhari, but that was a different city, a different Amritsar.

In the story of Ghulam Muhammad is the story of Lahore and Amritsar. It is the story of what the cities were, the story of their relationship, the story of their intermarriage. It is the story of what the cities are, of their antagonism towards fluid identities, of their newly discovered loyalties. The death of Ghulam Muhammad is the death of these two cities, of what they had been, of what they could have been.

Haroon Khalid

Haroon Khalid has an academic background in Anthropology and has been a travel writer and freelance journalist since 2008, traveling extensively around Pakistan, documenting historical and cultural heritage. His first book A White Trail: a journey into the heart of Pakistan’s religious minorities was published in 2013. His second book In Search of Shiva: a study of folk religious practices in Pakistan was released in December 2015, and his third book Walking with Nanak was released in December 2016. Imagining Lahore: the city that is, the city that was, published by Penguin Random House in August 2018, is his latest book.