Sanam Sutirath Wazir’s, The Kaurs of 1984: The Untold, Unheard Stories of Sikh Women

Excerpts and Interview by Artika Aurora Bakshi ((with permission from HarperCollins India)

“Where were you when 1984 happened?” A question that caught my attention and made me pause. I was nine years old, enrolled at Sacred Heart High School in Dalhousie, living in the safety of a boarding school that felt like something out of an Enid Blyton novel. We had all heard about Operation Blue Star and the pogrom that followed Indira Gandhi’s assassination. As the years passed, I questioned what had happened in Amritsar, across Punjab, and—most importantly—to the Sikh and Punjabi community. The Kaurs of 1984 made me step away from the politics of it all and connect with the women who lost everything: their homes, their families, their pride, and their future.

A book like this demands reverence. The accounts—whether seen as suppressed testimonies or haunting memories—are heartbreaking, forcing readers to question the society we live in and the elected representatives who have torn the fabric of humanity for personal gain. Forty-one years later, justice remains elusive, leaving readers to wonder if the system has failed entirely. Yet, a conversation with the author offers a deeper understanding of the book and, perhaps, a glimmer of hope that history will not repeat itself…

From Pens to Guns

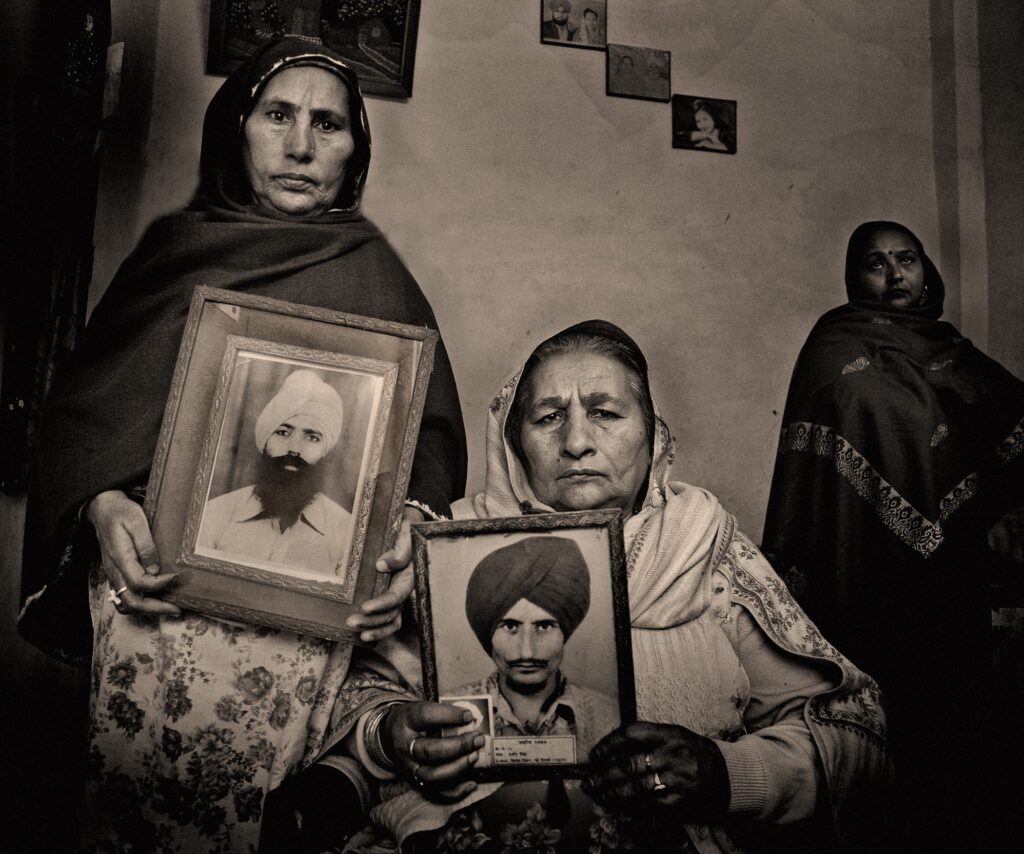

I met Darshan Kaur for the first time at her Rajaji Nagar home in Delhi, in 2016. I reached there around 7 p.m. with my colleague Sampurna Khasnabis. Darshan was waiting for us on the main road from where she took us into one of the congested lanes of the colony. Children were playing on the road in spite of the gathering darkness. Everyone seemed to know Darshan and we were stopped several times by neighbours wanting a casual, comforting chat. Darshan lived in a one-room flat which had an attached bathroom and a kitchen. She had done her best to make it a homely, cosy space. There was a single bed and a sofa set, and the walls were adorned with photographs of all the protests she had attended. The wall opposite her bed was an emptier one, with only a single garlanded photograph of a man on it. I asked Darshan whether this was her husband.

Biting her nails, Darshan nodded.Our conversation was difficult because of the depth and complexity of the emotions involved. Darshan found it hard to express what she had gone through in words and she broke down several times during the course of that first conversation. But one question that she asked me continued to reverberate throughout my research, and indeed, during the writing of the report on the subject, and now, finally, this book:

‘Successive governments have advised us to forget the past and focus on the future. Put yourself in our shoes for a second. Is it possible to erase the bloody past?’

As I leafed through the dossier, I realized how similar the path of history and politics is across the world, and how easily women become the first casualty of every conflict, large or small.

Rape and gendered segregation are common weapons of war and ethnic cleansing.

‘On 1 November 1984, my husband was attacked with swords and sticks; he lay on a charpoy in a vegetative state for three days after that. Our children sat with him, refusing to leave him. On the third day, a mob barged into our home and killed him. We lost everything in 1984. Our future, our right to progress, everything.

My younger son was in a depression for a long time. One day, he left the house and never returned,’ says Joginder Kaur. It is fair, then, to say that the agony of 1984 has not simply ended with those who lived through those times. If anything, the trauma has descended through succeeding generations, with the children of survivors suffering the untold consequences of the violence wreaked upon their elders.

‘I remember hearing the news of violent clashes around my place, but I wasn’t worried about us because we did not kill Indira (Gandhi). In some time, however, I realized my mistake. Even the police did not protect us; they were equally complicit in what became a massacre. I can clearly recount how my son and husband were beaten to death with sticks. I left my home with some money and gold. But later, all of my belongings were stolen, and the perpetrators tore my clothes,’ Shamni Kaur, another survivor of 1984, told me.

She continued, ‘We spent three nights in Chilla Gaon to stay away from what was happening. It has been thirty-five years with no justice whatsoever. We feel helpless. The mob killed our men and raped our women. Our people were burnt to death and our houses were looted. However, the custodians of our protection did not care. It felt like Partition all over again, when nobody cared for the common people.’

Today, there is a kind of restiveness among the Sikh community, both within the country and amongst the Sikh diaspora, over the inexplicable delay in delivering justice to the victims of the 1984 massacres. The first and second generations of victims have grown

up to be bitter and angry citizens, and an embittered population is not good either for long-term peace or for the stability of the country. It would be prudent for any government to catch early

warning signals when it comes to its people. Those among the culprits who are still alive, must, therefore be punished, failing which, a bad precedent would be set.

That was the first time that Darshan realized that Indira Gandhi was dead. ‘I felt my grandmother’s pain at that time. She walked from Pakistan to India, searching for a place she could call home. She thought she would be safe in India. But are we? We were no less than refugees in our own country. We were abandoned. We never mattered.’

From the foreword by Uma Chakravarti “Sanam’s book The Kaurs of 1984, through its narratives, picks up on many threads opened but not fully explored to date. It includes for the first time, in my knowledge, the terrible violence suffered by women caught in the vortex of happenings which were not of their making; women who were in the Golden Temple when

Operation Blue Star was launched in June 1984; and women who were mourning for Indira Gandhi on the morning of 1 November because they were her supporters—she had given them plots of land that made them independent homeowners for the first time. Some were even observing a fast. But they were mercilessly killed nevertheless.”

What prompted this book?

I started researching for Amnesty International, and realised that large-scale violence, especially in South Asia, often overlooks the aftermath for women. Historical records focus on numbers—how many men were killed—but the suffering of women, including sexual violence and displacement, is rarely documented.

During my research, I saw firsthand how women were left to fend for themselves, struggling for survival, justice, and recognition. I didn’t write this book to prove literary skill—I wrote it to document history that should not be forgotten. Even before securing a publisher, my priority was ensuring these stories were told, whether through a book, an online platform, or a podcast.

How do governments react to discussions on 1984?

Governments have historically used mass violence for political mileage. While some statements have acknowledged the attacks, justice has been delayed or selectively served. The struggle for recognition has been led not by governments but by the survivors—particularly women—who never stopped speaking out. However, true justice goes beyond convicting perpetrators; it includes reparations and helping victims rebuild their lives, which hasn’t happened.

Your book also discusses those who chose to participate in events leading up to 1984. How do you differentiate between them and the victims?

It’s a global issue—when young people get angry, governments often respond with crackdowns, further alienating them. Many who picked up arms in Punjab told me they felt it was their only option. The crackdown made them feel harassed, targeted, and trapped. While I don’t justify any side, my focus was to understand their motivations and give voice to all perspectives.

You initially started this work for Amnesty International as a report, not necessarily from a Sikh perspective. Your book primarily focuses on oral history with little personal opinion. Given the delayed justice and lack of meaningful compensation, how should governments learn from this?

Comparing Punjab of 1984 to Punjab of 2025 isn’t entirely fair. The 1984 Punjab was marked by intense fear, displacement, and restrictions. Today, while there are law and order concerns, the primary challenges are economic and environmental. The fiscal deficit and climate change are major issues, making the situation multi-dimensional. If these issues are looked into by the relevant authorities, we can avoid history repeating itself.

What do you hope to achieve from your book?

Regarding the impact of books like mine, beyond archiving, they serve as historical records. Conflict documentation is often inadequate, with few accessible records. The publishing industry rarely revisits past violence unless new dimensions emerge. Online archives, too, are fragile and often lost.

My connection to 1984 stems from growing up in a Sikh family that wasn’t directly affected but carried the trauma of 1947. Our family never spoke about Partition but felt deeply about 1984. I remember visiting the Golden Temple with my mother, seeing her emotional reaction to the bullet marks. Additionally, we lost two cousins in communal violence in Jammu in 1989. This underlying fear of backlash influenced my decision to write this book.

More than just preserving history, we need to learn from it—something the world consistently fails to do. Events like 1984 should have physical reminders, monuments in major cities, ensuring such tragedies are not repeated against any community.

Lastly, I’ve realized how important it is to keep exploring new ideas despite opposition. When I started writing about 1984, it wasn’t initially from a women’s perspective; that evolved over time. A mentor once told me that every idea deserves space at the table—without fear, bias, or the need for validation. That’s a philosophy I continue to follow.

Sanam Sutirath Wazir, a committed advocate for human rights from Jammu and Kashmir, is deeply engaged in documenting historical injustices and large-scale violence through oral history. He has successfully mobilized support from over half a million people across the world in advocating for justice for the victims of anti-Sikh massacres. His works, including ‘An Era of Injustice for the 1984 Sikh Massacre’, ‘The 1984 Sikh Massacre as Witnessed by a 15-year-old’ and ‘The Continuing Injustice of the 1984 Sikh Massacre’, are published by Amnesty International, etc.

(All images by Malkiat Singh, except Book Cover image)