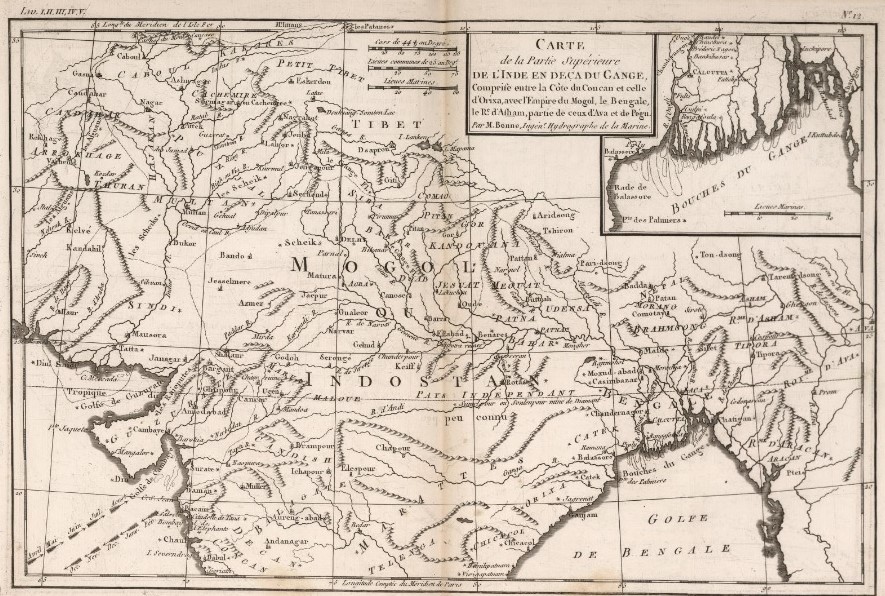

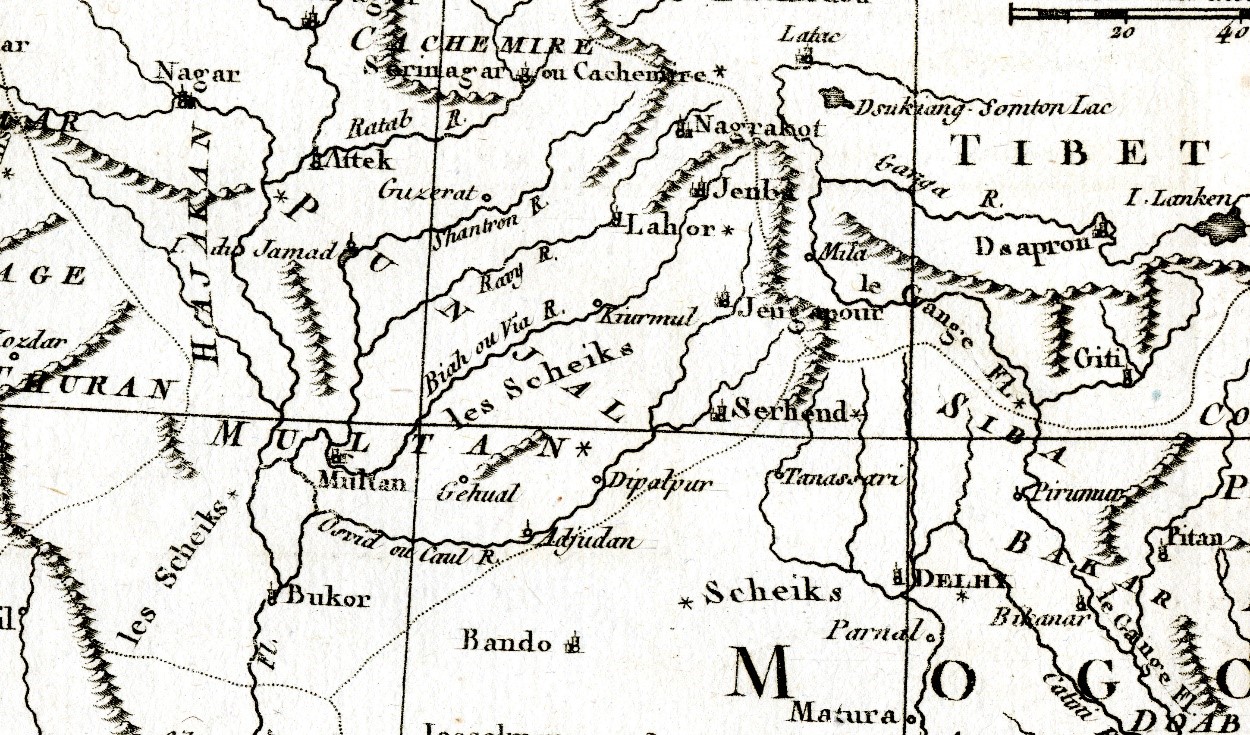

Synopsis: This article examines a sketch of the Sikhs in Abbé Raynal’s 18th century treatise, ‘Histoire Philosophique et Politique ….. dans les deux Indes’. Raynal notes the principal ideas of the Sikhs, radical in their modernity, and outlines their struggle for survival and subsequent emergence as a regional power. Raynal’s account of the Sikhs is reflected in the Atlas by Rigobert Bonne that accompanied the final edition of the Histoire. The map of India in Bonne’s Atlas carries the legend ‘les Scheiks’, making it one of the earliest maps to carry an explicit reference to the Sikhs.

One of the earliest maps to carry an explicit reference to Sikhs is in an atlas published in France in 1780. An early reference to a people is interesting, and in this case also intriguing as the Sikhs had not yet established a political state, nor were they a sufficiently populous group to warrant mention on a map.

The genesis of this map is an 18th century study of European settlement and trade in the ‘Indies’ by a certain Abbé Guillaume–Thomas Raynal.

Abbé Raynal and the ‘Histoire’

Educated by the Jesuits in France, Abbé Raynal left religious life to pursue a literary career in Paris. After some minor successes, Raynal gained wide recognition with the publication of his treatise: ‘Histoire Philosophique et Politique Des Établissemens et du Commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes’. The Histoire is a survey and critical assessment of European and British commercial and colonial ventures in the ‘Indies’, a label loosely applied to countries in Asia, in the Americas, even Africa.

First published anonymously in Amsterdam in 1770, a revised edition of the Histoire was issued at La Haye (The Hague) in 1774. This was followed by a substantially expanded third edition published in Geneva in 1780. This – the final edition – was supplemented by an atlas by the cartographer, Rigobert Bonne.

The success of the Histoire was immense. In its first two decades alone, it is estimated that the book had thirty authorized printings (and forty pirated printings) in the principal languages of Europe, making it among the most well–known works of its time. [Womack 1970, p.3].

An English translation of the 1774 edition of the Histoire appeared in 1776. The translation of the definitive 1780 edition followed in 1783, with seven maps by the English cartographer, Thomas Kitchin, in lieu of the Atlas by Bonne. In his examination of colonial practices, Raynal denounces slavery and decries the injustice and cruelty that accompany colonization, and religious intolerance which underpins it. The critical stance of the Histoire towards prevailing policies in ‘les deux Indes’ placed it at odds with vested interests, commercial and political. The Histoire came to be seen as subversive, a precursor of radical ideas that would soon animate the French Revolution. The Church caused the book to be banned in France and its author exiled.

L’Indostan

Among the countries examined in the Histoire is ‘l’Indostan’, India. Raynal provides a natural history of the land, its great rivers, its coasts and the Deccan hills that separate them; and proclaims it ‘the most fruitful country in the world.’ [Raynal 1783, v1, p50].

He describes the trading footholds of the European powers – Portugal, Holland, France and Britain – along the coasts of India. He notes their growing influence in India and their rivalries, and decries ‘the rage of conquests, and what is no less destructive an evil, the greediness of traders’ that have ravaged the country [Ibid, p5].

In a wide–ranging account of the civil code that governs Hindu life, the author remarks on the caste system and its inequities: ‘the most ancient system of slavery’ [Ibid, p58]. He surveys the science and the mythology of the people, and examines with serious interest the language, Sanskrit, as a vehicle for philosophy and literature.

The rulers of the greater part of the land – the Mughal emperors in Delhi – are reported from a distance. The Histoire speaks of the opulence of the imperial court and its arbitrary exercise of power; and observes the diverse people in Mughal dominions and beyond: the Rajputs, the Mahrattas, the Pathans and, among others, the Sikhs.

A new nation: Les Seicks

Appearing first in the 1774 edition of the Histoire, and repeated in the final 1780 edition, is a sketch of a people largely unknown at the time in Europe:

‘To the north of Indostan there is a new nation of people even more formidable (than the Pathans). These people known as Seicks have learned to do away with despotism and superstition, even though they are surrounded by enslaved nations. It is said they are followers of a philosopher ……who gave them ideas of freedom, and taught belief in Deism with no hint of superstition’ [Raynal, 1780, v2, p298].

The land ‘north of Indostan’ is the Punjab, home to the Sikhs, people of a monotheistic faith founded in the 15th century. Infused with ideals of equality and social justice the Sikhs had evolved, by the close of the 17th century, into an egalitarian fraternity with a scripture, a language, and a well–defined identity. Raynal’s account of the Sikhs is brief but acute in its remarks on their resolve, and on the sovereign status accorded to their scripture: ‘They are said to be firm in their faith, and in their temple is an altar on which is placed their book of laws …. which is the supreme sovereign of their republic’. A notable aspect of Raynal’s remarks is the absence of the exotic. There is, for instance, no mention of the distinctive appearance of the Sikhs, of turbans worn over their long un–cut hair. The attention instead is on their ideas. The growing Sikh movement attracted in the 17th century the attention, and eventually the hostility of the ruling power, the Mughals. The death at Mughal hands of two of the spiritual leaders (‘Gurus’) of the Sikhs was cause for antipathy towards the regime, and eventually an uprising in the early 18th century.

The Edict of Genocide

The Sikh uprising saw initial successes but was eventually suppressed, the rebel leader tortured and put to death in public; and his soldiers executed en masse. The executions were followed by an imperial edict of genocide: ‘every Sicque should, on a refusal of embracing the Mohametan faith, be put to the sword. A valuable reward was also given by the emperor for the head of every Sicque ….’ [Forster 1798, v1, p271].

The Mughal edict of 1716 gave sanction to what in fact was already a practice. The half–century that followed saw the Sikh struggle for survival and the genesis of a nation state.

According to the Histoire: ‘They (the Sikhs) began to be known at the beginning of the century, though they were then regarded less a nation than a sect. Under the miseries of Mughal rule, their numbers grew considerably with converts from other religions who joined them to find refuge from the oppression and furies of their tyrants’ [Raynal 1780, v2, p299]. The resistance against ‘the oppression and furies of their tyrants’ took a turn in 1739, with the invasion of India by Nadir Shah of Persia. The destruction that attended the invasion was great; more significant politically was the damage to Mughal authority. That authority would be further battered by Ahmad Shah Abdali, an Afghan protégé of Nadir Shah and his trusted aide in the invasion of India. A palace coup in Persia caused Abdali to flee to Kandahar in 1747. Proclaimed ruler of Afghanistan by his band of followers, Abdali set out to take Lahore, rich capital of the Mughal province of Punjab. The invasion brought him up against the Sikhs.

Formation of the Sikh Misls

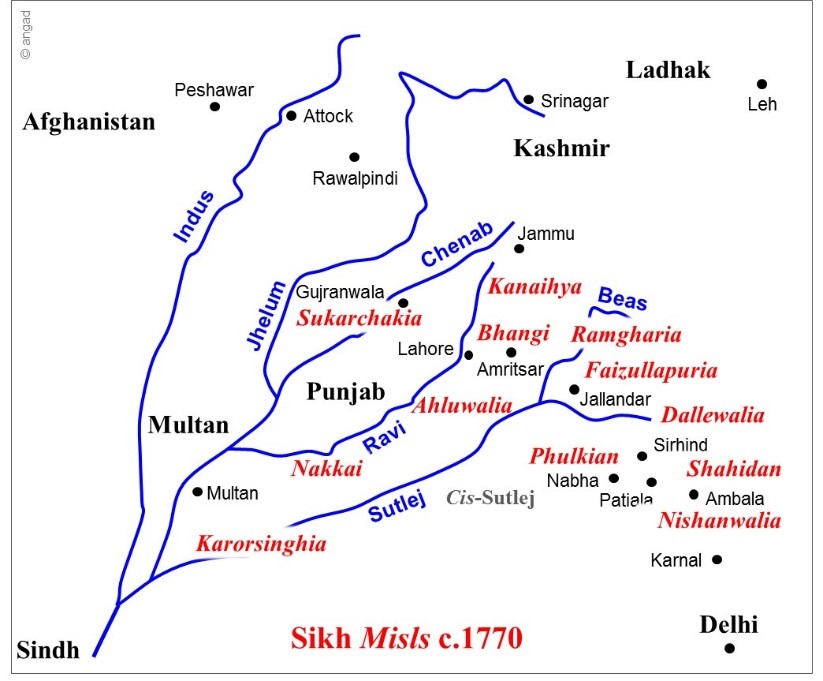

The violence that followed the Mughal edict of genocide had led the Sikhs to gather in defensive bands, ‘jathas’. In the face of yet another adversary – the Afghans – the bands coalesced into larger battle groups. At a landmark meeting in 1748, the jathas came together as a Sikh army, the Dal Khalsa, that organized itself into eleven divisions which came to be known as ‘misls’, or ‘misals’.

Famously described as ‘confederacies of equals, under chiefs of their own selection’ [Prinsep 1834, p. 29], the misls were self–governing bodies, each member within it ‘an equal among equals.’ A child of necessity, the misl would play a pivotal role in the history of the people and in the formation of a state.

The battle groups of the misls consisted mainly of cavalry, the horsemen equipped with whatever weapons each could muster, mainly muskets and the customary hand weapons. Lacking heavy ordnance, the misls had the advantage of speed; another advantage unseen was tacit support of the peasantry.

In the main, the strongholds of the misls lay between the Indus River and the foothills of the Eastern Himalayas (Figure 2), an expanse often loosely described as ‘greater Punjab’. The largest and initially the most prominent battlegroup consisted mainly of cavalry, the horsemen equipped with whatever weapons each could muster, mainly muskets and the customary hand weapons. Lacking heavy ordnance, the misls had the advantage of speed; another advantage unseen was tacit support of the peasantry. In the main, the strongholds of the misls lay between the Indus River and the foothills of the Eastern Himalayas (Figure 2), an expanse often loosely described as ‘greater Punjab’. The largest and initially the most prominent battlegroup was the Bhangi misl, centered in Amritsar. The overall command of the Dal Khalsa was entrusted to an emerging leader, Jassa Singh of the Ahluwalia misl. South of the Sutlej River lay a twelfth misl, the Phulkian, which remained for most part at the periphery of the Sikh struggle. Independent entities, the misls were informally bound by a common imperative of defense. They convened at regular intervals – by custom in Amritsar – on matters of common interest, mainly military. Resolutions (gurmata) struck at these public assemblies were morally binding, foreshadowing a future ideal of governance: of popular engagement and consensus, in principle if not always in fact. Vastly inferior in weaponry and numbers to the ruling Mughals, and to the invading Afghans, the misls would prove to be an obstacle, and eventually a challenge, to both.

The Afghan Invasions

Abdali’s march to Lahore in 1747 was but a step in his road to the Mughal capital, Delhi. It was the first of a series of invasions – ten in all – over the next two decades. The Afghan armies would typically set out at the start of winter and return to Kandahar before the heat of high summer in India. The Afghan invasions are best understood as large–scale raids to replenish the treasury of Abdali’s newly established kingdom.

Territories in India were overrun with impressive ease but there was little attention paid to consolidating the gains. The task of governors installed by Abdali in subjugated provinces was primarily to guard and oversee the extraction of wealth; civic matters were left to existing structures. Under the brunt of successive invasions, the Mughal regime began to give way to Afghan demands. Revenues from ‘Chahar Mahal’ – ‘four palaces’, the cities of Aurangabad, Pasrur, Gujrat and Sialkot – were turned over to Abdali. Also relinquished shortly after was Mughal sovereignty over the province of Multan. Further reverses forced the Mughals to formally surrender Lahore – in effect Punjab, its vital frontier province – in 1752. The Afghans went on to also take the contiguous northern province of Kashmir.

Abdali faced no opposition when his army eventually entered Delhi in 1757. A spark of resistance by citizens triggered a plunder of the capital, followed by the pillaging of other cities in the region. Abdali’s son, a minor, was appointed Viceroy; and the district of Sirhind annexed to the Afghan kingdom. A fresh challenge to Abdali arose from the Mahrattas, a Hindu power in the Deccan with ambitions (and a brief history) of occupying the Punjab. The crushing defeat of the Mahratta army at Panipat in 1761, removed the last of the region’s rulers to militarily oppose the Afghans.

Resistance in Punjab

Raids on the Afghan army in its marches through the Punjab marked the war of resistance waged by the Sikh misls. On the heels of that army’s return to Kandahar, the misls stormed territories under Afghan jurisdiction, ejecting the appointed governors, ‘throwing them out, like flies out of milk’ [Grewal and Habib 2001, p181]. The collapse of order in the province gave rise to ‘rakhi’, an arrangement by which the misls undertook to defend villages for a ‘moderate rent, and that mainly in kind’. A source of revenue for the misls, this development also spoke to a certain shift in authority, the misls encroaching on revenues previously claimed by Mughal Delhi.

After Panipat, the struggle for Punjab became essentially one between the Afghans and the Sikhs. Still no match for Abdali’s army, the misls were an increasingly serious obstruction, often holding their own against the Afghans (and at times their provisional allies, the Mughals).

In a surprise maneuver in 1762, Abdali fell upon a misl encampment near Sirhind. It was the most punishing loss suffered by the Sikhs in the history of the struggle, and is remembered in Sikh annals as ‘Vadda Ghallughara’, the great carnage. The Afghans went on to desecrate and demolish the Sikh shrine at Guruchak, the future city of Amritsar.

In turn, the misls laid waste to settlements of the Afghans and their vassals and allies in north India. The scale of destruction impelled Abdali to invade the country again, this time in military alliance with neighboring Baluchistan. The combined armies were unable, in the face of fierce resistance, to make headway beyond Sirhind. Abdali’s cycle of invasions to gather tributes and monies ‘owed’ by subjugated regions were now increasingly about battling the misls.

The capture of Lahore by the misls in 1765 was a turning point, a triumph proclaimed by the minting of a Sikh coin. The inscription on the coin invokes the Sikh Gurus. Also inscribed are the words “Deg, Tegh, Fateh”, each word charged with meaning:

• Deg, a cooking vessel – a promise to feed the populace

• Tegh, a sword – the strength to fulfill that promise

• Fateh, victory – success in making good that pledge

The language acknowledges the sentiment and memory of the short– lived republic proclaimed by Banda Bahadur (footnote 6). Further invasions by Abdali and his successors still lay ahead, but much of Punjab was now held by the misls. Also within their reach lay Multan, even tracts of trans–Indus Afghanistan. The Afghan invasions were cause for concern to states beyond the Mughal dominions.

The ascendancy of the misls in the Afghan struggle was followed with close interest by powers in the region, Indian and foreign, especially by the British given their own territorial ambitions in India. According to a British dispatch, Lord Clive ‘is extremely glad to know that the Shah’s (Abdali’s) progress has been impeded by the Sikhs .….. as long as he (Abdali) does not defeat the Sikhs, or come to terms with them, he cannot penetrate into India’ [Gupta 1995, v2, p242].

Raynal makes no explicit reference to the misls but notes instead the collective military success of the Seicks who ‘can raise a cavalry of sixty–thousand good horse’, and ‘now possess the entire province of Punjab, the larger part of Multan and Sindh, both banks of the Indus River from Cashmere to Talta and the country towards Delhi from Lahore to Sirhind’ [Raynal 1780, v2, p299].

This broad assessment is closely reflected in the maps of India in the atlas by Rigobert Bonne that accompanied the final, 1780, edition of Raynals’s Histoire.

Rigobert Bonne : Atlas de Toutes Les Parties Connues du Globe Terrestre.

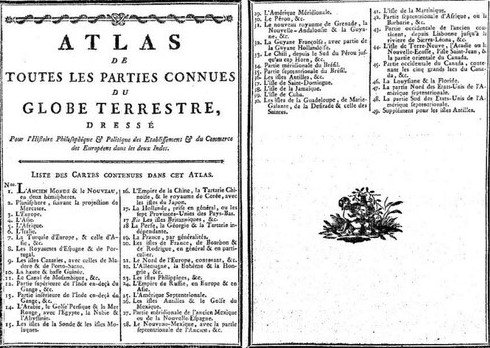

The final 1780 (Geneva) edition of Raynal’s Histoire was accompanied by an undated ‘Atlas de Toutes Les Parties Connues du Globe Terrestre’ by Rigobert Bonne.

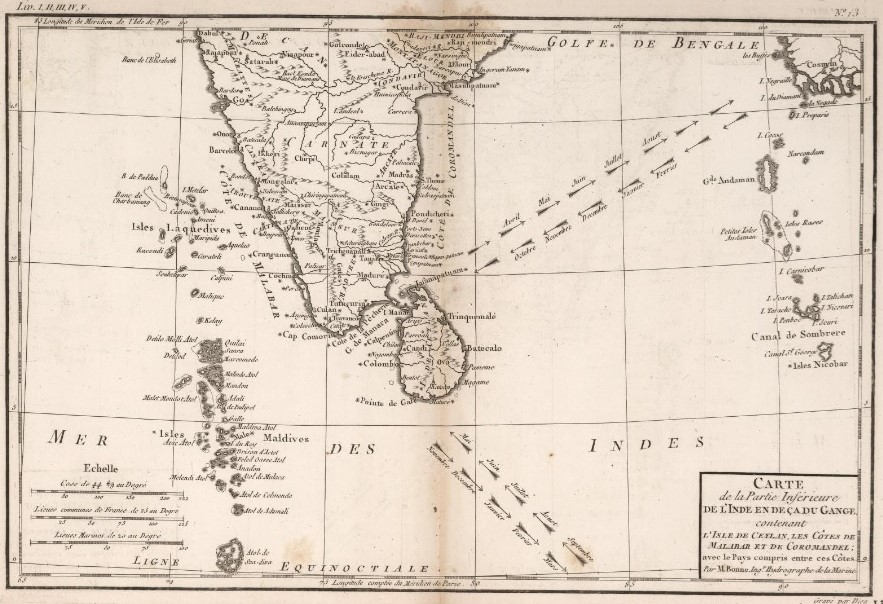

A mathematician and military engineer, Rigobert Bonne served as a cartographer in the Hydrographical Office of France and was appointed Royal Hydrographer in 1773. He contributed to maritime and geographical atlases and other publications (notably the 2–volume Atlas Encyclopédique), but he is best remembered for his Atlas that accompanied Abbé Raynal’s Histoire which had begun to gain renown. Bonne’s Atlas is prefaced by a 28– page ‘Analyse Succincte’, primarily cartographic source data for maps of the world. Also gathered in the Atlas are 23 tables of statistical data on trade by European nations – France, Britain, Holland, Spain and Portugal – in the diverse lands of ‘les deux Indes’. The main body of the Atlas consists of 49 double–page maps. Noted above each map is the ‘book number’ of the 1780 edition of the Histoire in which that region is discussed. People and place names that appear in Raynal’s text are highlighted in the maps with an asterisk (*). Absent in the maps in Bonne’s Atlas are the flourishes, the cartouche and the compass rose, of the more decorative maps of the era. The attention instead is on the technical dimension, on function and precision. The map of the southern peninsula carries more detail, the region being better known to European nations with their trading interests and outposts along the two coasts.

To that, Bonne adds useful information, notably the months and direction of the monsoon winds that regulate the agricultural seasons of India. Noted in both maps, in addition to geographical data, are the military forts in the land. The greater number of these appear, on cursory examination, in the map of North India, the battleground of historic invasions.

Map of North India detail – “les Scheiks”

A segment of Bonne’s map of North India, (Figure 4A), allows a closer examination of the region. Indicated on the map, albeit with a broad brush, are territories under the influence, and at times control, of ‘les Scheiks’. Explicit mention of the Sikhs appears at three points on the map of greater Punjab, misspelt here as ‘Punjal’. The label ‘Les Scheiks’ in the region below the Beas River (‘Beah ou Via R’) can be said to refer to the main body of the misls spread between the great rivers of Punjab (Figure 2).

These battlegroups, by virtue of their strength and location, were the most prominent in confronting the Afghans. They would later play prominent roles in the consolidation and founding of a political state. Another label ‘les Scheiks’ finds place south–west of Multan, in trans–Indus Afghanistan. The authority of the misls in the region west of the Indus River was tenuous, but it was enough to deter Abdali’s Baluchi military ally in the joint invasion in 1764 from accepting a gift of the ‘territory of Quetta …. and the adjoining territories of Derahs, Multan and Jhang, the whole country west of the Chenab, but the Khan … respectfully declined to accept this gift, most probably for fear of the Sikhs’ [Gupta 1995, v2, p224–225].

The third label ‘Scheiks’ is placed south of Sirhind, due west of Delhi. With their occupation of Sirhind and adjacent territories in 1764, the misls ‘carried their victories right up to Delhi and … into the heart of the Gangetic plain’ [Singh 1997, v3, p96]. Within three years of Bonne’s map, the misls would enter Delhi, the Mughal capital, itself. More than a show of strength, the entry of the misls into Delhi in 1783 was significant in that the misls compelled the Mughal ruler to assent to the building of gurdwaras on sites in the city sacred to the memory of their Gurus, most significantly the sites associated with the beheading of the ninth Sikh Guru by an earlier Mughal regime [Gupta, v3, p168].

The Emergence of the Sikh Misls

The text on the Sikhs in Raynal’s Histoire first appeared in the 1774 edition. The same text is repeated without change in the 1780 edition. The labels – ‘les Scheiks’ – in Bonne’s map of 1780 therefore refer to a reality of 1774.

By then, the misls had blunted the Afghan invasions; and, against a backdrop of a half–century struggle against the Mughal edict of genocide, had wrested control of sizeable territories from Afghan hands. With the capture of Lahore, the misls supplanted the Mughals as the de facto authority, if not yet rulers, of the Punjab.

Territories held by the Sikh misls – both banks of the Indus below Multan, and the Punjab plains north of the Sutlej – now formed the northern limit of the Mughal India. Hence, the Raynal reference to a ‘new nation … north of Indostan’.

The mention of ‘Scheiks’ in Bonne’s Carte de la Partie Supérieure indicates a seismic change, a shift in authority in regions nominally still part of ‘Mogol de Indostan’. Much of greater Punjab now lay under the influence and to some degree control of ‘les Scheiks’.

That control was still fluid, the boundaries neither clear nor constant. Minutiae in Bonne’s map, ‘les Scheiks’ acknowledge a new presence – military, political and social – in the ‘land north of Indostan’. It would be a few decades before ‘les Scheiks’ would coalesce into a nation state, but the transformation of the misls into sovereign entities had begun.

Postscript: Over the next two decades, the misls that comprise ‘Les Scheiks’ in Bonne’s map went on to consolidate their territories and assume broader powers of governance. Ranjit Singh, young heir to the Sukarchakia misl, set about bringing – through marriage alliances, diplomacy and muscle – the misls north of the Sutlej under his flag to establish what would become the kingdom of Lahore.

Acknowledgements

The English translation of the text in Raynal’s Histoire, (Geneva 1780, v 2, pp298–299) is by Marlène Lepage. All other quotations from the Histoire are from the Justamond translation, 1783.

Gratefully acknowledged are the resources and staff of the BnF (Bibliothèque nationale de France), Paris; Cambridge University Library, UK; Robarts Library and Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, both at the University of Toronto; the Toronto Public Reference Library; and the electronic archives of the University of Michigan, the University of Oklahoma and of the Metropolitan Library of New York. Also thanked is Prof. Harjot S. Oberoi (UBC) for helpful comments on this work.

This article is an abridged version of “The Emergence of the Sikh Misls – Abbé Raynal’s Histoire and a map by Rigobert Bonne”, B. S. Marwah, originally published in Sikh Formations, Volume 19, 2023–Issue 4. [https:/doi.org/10.10 80/177448727.2023.2023.2262146]

B.S. Marwah has served on Boards of academic and industrial organizations in Canada; and taught applied statistics at the University of Toronto.

Bonne, Rigobert. Atlas de Toutes Les Parties Connues du Globe Terrestre. Supplement to Guillaume-Thomas Raynal’s Histoire Philosophique et Politique des Établissements et du Commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes, 1780.

Dhavan, Purnima. 2011. When Sparrows became Hawks – the Making of the Warrior Tradition, 1699-1799. New York: Oxford University Press.

Forster, George. 1798. A Journey from Bengal to England: Through the Northern Part of India, Kashmire, Afghanistan, and Persia, and Into Russia, by the Caspian-Sea. London: Faulder.

Grewal, J. S. and Habib, Irfan. 2001. Sikh History from Persian Sources. New Delhi: Tulika.

Grewal, J.S. 1999. The Sikhs of the Punjab. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gupta, Hari Ram. 1944. Studies in Later Mughal History of the Punjab. Lahore: Minerva.

Gupta, Hari Ram. History of the Sikhs, Vols.1-5. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.

– Vol. 1: The Sikh Gurus, 1469-1708. 2nd revised & enlarged edition, 2000

– Vol. II: Evolution of the Sikh Confederacies. 3rd revised edition, 1978

– Vol. III: Sikh Domination of the Mughal Empire. 3rd edition, 1992

– Vol. IV: The Sikh Commonwealth or the Rise and Fall of the Sikh Misls. 1995

– Vol. V: The Sikh Lion of Lahore (Maharaja Ranjit Singh, 1799-1839). 1991

Princep, Henry T. 1834. Origin of the Sikh power in the Punjab and the political life of Muha-Raja Runjeet Singh. Calcutta: G.H. Huttman. Military Orphan Press.

Raynal, Guillaume-Thomas. 1774 Histoire Philosophique et Politique des Établissements et du Commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes, Vol.s 1-6. La Haye: Chez Gosse et fils.

Raynal, Guillaume-Thomas. 1776. A Philosophical and Political History of the Settlements and Trade of the Europeans in the East and West Indies, Vols. 1-4, trans. J. Justamond. London: T. Cadell.

Raynal, Guillaume-Thomas. 1780. Histoire Philosophique et Politique des Établissemens et du Commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes, Vols. 1-10. Geneva: Pellet.

Raynal, Guillaume-Thomas. 1783. A philosophical and political history of the settlements and trade of Europeans in The East and West Indies, Vol. 1-10, trans. J. Justamond. London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell.

Singh, Khushwant. 2004. History of the Sikhs, Vols. 1-2. New York: Oxford University Press.

Singh, Harbans (ed.). 1997. The Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Vol. 1-4. Patiala: Punjabi University.

Womack, William Randall. 1970. Eighteenth-Century Themes in the ‘Histoire Philosophique et Politique des deux Indes’ of Guillaume Raynal. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oklahoma.

***********