Interview by Artika Aurora Bakshi

I have walked the streets of Amritsar, awestruck by the intricate jaaliwork of the jharokas in the old mansions, the carvings on the entrance pillars, and the dates written on the facades. This feeling is always followed by a deep sadness at the state these havelis lie in. Punjab, both sides of the border, is dotted with monuments from the times of glory, but they lie in ruin, with very few being taken over by the authorities or private organisations. Restoration, and conservation are issues that are close to our hearts, and we at Nishaan have been highlighting these. In our endeavour to create awareness, and bring these issues to the forefront, here is another feature, hoping that those who can make a difference take note before the forgotten history, manuscripts, artefacts, and monuments are lost forever. For the Anglo-Punjab History enthusiasts, Peter Bance is not a new name. His Instagram account is fervently followed by many, with each of his posts generating thousands of engagements.

It all started with a trip, around twenty five years ago, when after a conversation with my parents, I wanted to visit the resting place of Maharaja Duleep Singh in Thetford. While there, I was pointed towards a small museum by an elderly lady.

The museum had been started by the late Maharaja’s son, and showcased memorabilia connected with the lives of the Maharaja and his children. Further intrigued, I asked the curator if there was any literature dedicated to his family, old records etc. The answer in negative prompted me to place a series of adverts in the local papers, asking if anyone had known or had any information about the family. Over the next six months, I received close to three hundred replies from people. Some had known the children, some, whose grandfathers had worked for the Maharaja, and some who had things that had belonged to him, like diaries, hunting boots, photo albums etc. I spent that year visiting these people, collecting information, and even buying some of the memorabilia. Some of the people just gave the things they had, because they saw how appreciative I was of the history associated with the items.

Since all the children had died without any heirs, a lot of their things were taken away by the locals,or the people who worked for them. So many years later, the descendants had no attachment to those items, and this enabled me to build up a collection, fuelling my interest to record and preserve the history of the Sikh Darbar and Maharaja Duleep Singh, and how he and his descendants had lived in England. It took me almost two years to come up with my first publication.

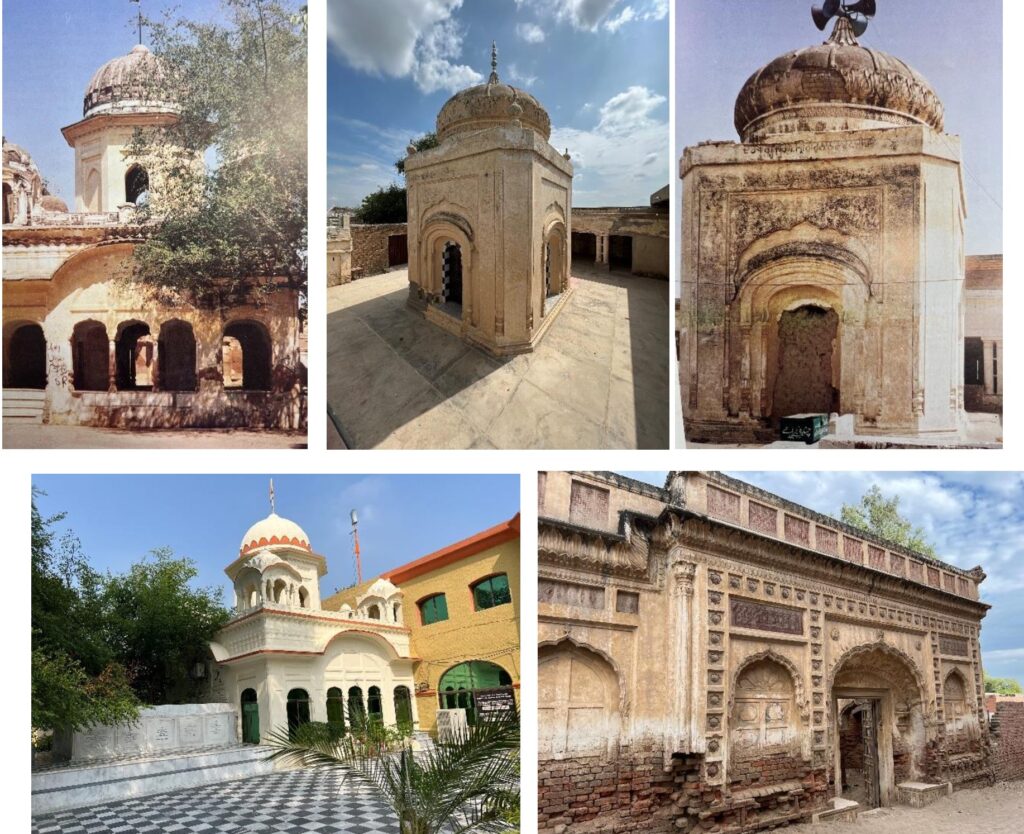

To understand Maharaja Duleep Singh, and trace back his life when he was a child in India, Peter travelled to Lahore in 2004, and this led him further to discover the splendour of the Sikh Darbar through the monuments that stood witness to the Sikh Empire of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The state these monuments were in, was another story.

My family has its roots in what is now Pakistan, just like the family of the Maharaja I was researching. My grandfather left Sialkot in 1936 to come to England. The first thing I did was to visit my grandfather’s house, and then further to Gujranwala, Lahore, and all the other places associated with Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Maharani Jind Kaur, and Duleep Singh. From then on, I regularly visited India and Pakistan, realising that a major chunk of monuments relating to the Sikh Empire are in Pakistan, in the Punjab there. To understand nineteenth century Punjab, one has to visit Pakistan, to see the monuments, which are a prime example of Sikh architecture.

The first reaction on seeing the monuments is despair, at the state they are in. Looking at them in a wider context, one feels glad that they still exist, though it is sad that in the region where most of the Sikhs live, as opposed to the region across the border, in the name of restoration, many monuments have lost their originality. The old ones have been demolished, new ones, modeled on the Sikh architecture having taken their place. The historical character of the building gets lost, the Nanakshahi bricks, which were the trademark of architecture from that period,replaced by marble and gold.

THE WAY FORWARD? MAKING OUR VOICES HEARD…

It’s heartening to see the restoration of the Sikh Gallery in the Lahore Fort, and the preservation of buildings in the walled city of Lahore. It seems that there are voices being heard. A team from Europe, specifically from Hungary has been hired to restore the paintings of August Schoefft.

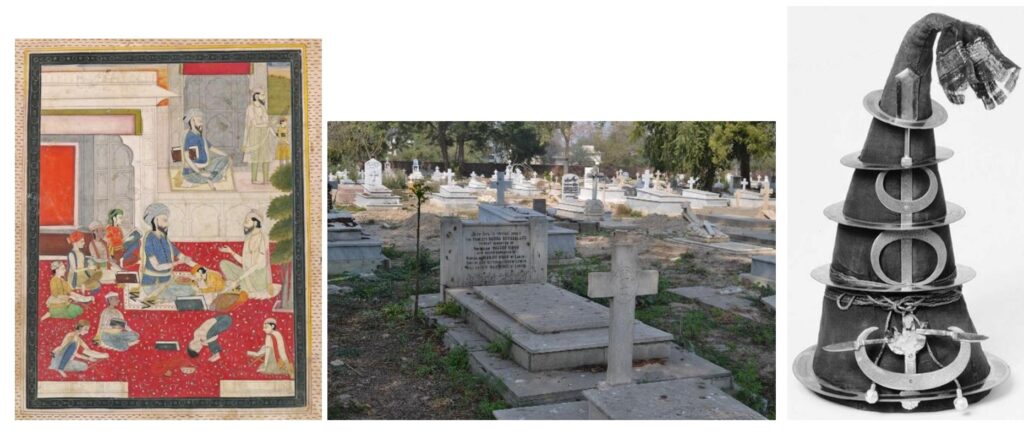

August Schoefft (1809 – 1888) was a Hungarian painter of the 19th century. He spent more than one year in the Sikh Empire, arriving in 1841, where he painted portraits and scenes of the surrounding area. His best known works include The Court of Lahore and Maharaja Ranjit Singh at Darbar Sahib.

I want to see more work done in India. Since the Sikh population in India exceeds that of Pakistan, there is awareness about who Maharaja Ranjit Singh was, and how grand the Sikh style of architecture was. Funding is not the issue. For historical preservation to gain momentum in India, it is important that private enthusiasts and governmental bodies work together. The awareness needs to spread to the grassroots. On my visits to Lahore, I met a few historians who were researching and cataloging artefacts, documents, and buildings of the Sikh Darbar. This is one way of creating awareness. They actively share their work on the digital platform, hence the new approach to preservation there. The way forward is by networking, and using technology to spread awareness, share research, and by doing so, adding to archives. This also encourages tourism, which further encourages preservation and restoration. While we are talking about monuments, let’s not forget the historic gurdwaras. The prime example is Kartarpur Sahib. Sikhs from all over visit, and take pride in the history of the gurdwara.

Using his Instagram account, Peter Bance is bringing these forgotten and neglected monuments into the limelight. Awareness created through online engagements, is his way of sharing his passion for Sikh history.

By pure accident, I started creating awareness. It all started with me wanting to know more about the Sikh Darbar. The lack of archives prompted me to document my findings, and my visits to Pakistan and India, mainly the places connected with the Sikh Darbar, gave birth to my Instagram account. and people started approaching me about restoration. I had to tell them that I was not a restorer, but because of the power of digital technology, people who were interested in taking this forward could connect. People have reached out and brought places to my attention. Every week I get hundreds of messages from people on both sides of the border, asking me to let them know next time in the area, to show monuments which lie forgotten. These people sadly are not in positions of power to take up such projects. I am hoping that those in seats of power take these causes up, the governments, different organisations involved in heritage restoration and conservation.

Every individual with a passion for history speaks sadly about what is lost. While disheartened, with voices not being heard, they still carry on in their own way, trying to make a difference. How many more monuments do we need to lose before we wake up? We talk about bringing back the museum pieces from the U.K. and Europe, about the Koh-i-Noor, the throne of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the jewels and the tapestries which adorn the walls of museums outside the historical region, but sadly, what was left behind has not been cared for.

Let’s not forget, not all the things in museums abroad were stolen from India. Emissaries were showered with gifts by the monarch when they visited the darbar, the same way as the maharajas were honoured with gifts from abroad. The sad thing is that while these things were looked after by the British, the gifts that came to Lahore for example, were not kept in the same way. Hence, we see that more artefacts are found in Britain than in India and Pakistan. Many of these high-value items, which were owned by some of the princely houses of Punjab, have been auctioned. After 1947, when many of the royal houses should have handed over their treasures to the government, they sold their possessions privately to generate funds. Private collectors, and museums abroad, like the Victoria and Albert, are ensuring that they look after their collections, most of it obtained through proper auctioning processes. Museums in the U.K. also ask the collectors to lend their collections for specially-curated exhibitions.

Peter Bance’s endeavour, and his commitment is awe-inspiring, and by showcasing passionate individuals like him, those who are proud of their heritage, we at Nishaan can only hope that the voice we raise does not fall on deaf ears.

Peter Bance is an independent researcher, author and historian, emphasising much of his work around Anglo-Punjab History. He operates a London-based property business, but has a deep affection for history, strongly believing in the restoration, preservation and recording of historical events and data.

Peter is a UK-born Sikh, whose family was among the early Sikhs to migrate to Britain in the 1930s. As a third generation UK Sikh he has great affection for his ancestral homeland and annually visits the West and East Punjab to research its rich and colourful history. His research has allowed him to locate and acquire the largest collection of memorabilia and artefacts associated with Maharajah Duleep Singh and his family, which he has built over the last two decades. Amongst his collection is original clothing worn by the Maharajah, his personal diaries, his bible from Fatehgarh and personal family photo albums.

He has written a number of books on Anglo-Sikh subjects with major publishing houses, and contributed to countless publications with his research and photographic archive.

Published works:

2004 The Duleep Singhs: Photo Album of Queen Victoria’s Maharaja, (Sutton Publishing)

2007 The Sikhs in Britain: 150 Years of Photographs, (The History Press)

2008 Khalsa Jatha Centenary 1908-2008, (KJBI)

2009 Sovereign, Squire & Rebel: Maharajah Duleep Singh the Heirs of a Lost Kingdom (London, Coronet House)

2010 Phillaur Fort – The Fort of Maharajah Ranjit Singh, Co-author. (Punjab Police Academy)

2012 Sikhs in Britain, New Edition, (London, Coronet House)

2016 Visualising a Sacred City; London, Art and Religion, co-author (IB Tauris)

2017 Sikh Art from The Kapany Collection, co-author, (Sikh Foundation)

Select Television & media work:

2004 Granada Television & History Channel, interviews on Maharajah Duleep Singh

2005 BBC1 Inside Out, Documentary presented by Gurinder Chadha. (consultant and interview)

2006 BBC2 Desi DNA with Hardeep Kohli. (contributor and interview)

2009 BBC1 The One Show, feature on Maharajah Duleep Singh. (consultant)

2010 BBC1, ‘Remembrance –The Sikh Story’. Consultant, contributor and interview

2011 BBC1, Hidden Painting of the East, with Meera Syal. Contributor and interview

2012 BBC1, ‘Story of the Turban’ documentary. Contributor and interview

2013 BBC1, ‘Britain’s Maharajah’ documentary, contributor & Interview

2014 BBC Radio4, Exhumations of a Maharajah, contributor & interview

2015 BBC Antiques Roadshow – India Special

2017 ITV National News, Interview by Nina Nunnar on Maharajah Duleep Singh

2017 The Black Prince, Hollywood production feature film (consultant)

2018 BBC3, The Lost Maharajah – consultant and interview

2022 Australian ABC TV, ‘The Things the Raj Stole’

2022 C4, ‘Queen ‘Victoria’s British Maharajah’ with Gurinder Chadha

2022 BBC2 Antiques Road Trip – Catherine Duleep Singh (interview) Series 25 Ep1

2022 BBC World Service at Archive Centre Norwich

2023 BFI film ‘Kaur’ on Duleep Singh princesses, Consultant, executive producer

He regularly contributes to BBC Radios Suffolk, Norfolk and London.

He is currently part of a British Film Institute film on a joint British-India production which covers the Suffragette life of Princess Sophia Duleep Singh.