Early relations between the United States and India are yet to be fully assessed, particularly in their triangular connections with France in the aftermath of the Treaty of Versailles (1783). The result of this treaty was the exit from the British Empire of a new world power in North America. But in this same period, in Asia, almost every Indian state quickly passed under British hegemony between 1792 and 1818. With the lone exceptions of Punjab and Sindh, the map of the subcontinent was increasingly “turning red,” the color of British territories.

The capitulation of Lord Cornwallis to Washington and Rochambeau at Yorktown on October 19, 1781, and the 1783 Treaty of Versailles which gave birth to the United States of America left a lasting impression on the minds of British officers in charge of India. After Yorktown, Lord Cornwallis went to India, where he was appointed governor-general thrice—and commander-in-chief twice. He died in India in 1805. His obvious task was to prevent India from following the path of America. In 1795, when Lord Wellesley was sailing to India to assume his governorship, he wrote about French and American agents at work with Scindhia in Northern India in order to malign the East India Company. In September 1803, Delhi was captured by the British after the battle of Patparganj. The victor, Lord Lake, commander-in-chief of the British armies in India, was a former officer of Cornwallis in North Carolina, and the officer he appointed as the first British Resident in Delhi was Colonel Ochterlony, who later became famous in the Anglo-Nepalese War and is still remembered today by the mighty column erected in his honor on the maidan adjacent to Esplanade in downtown Calcutta. Ochterlony settled in Delhi in what remained of Dara Shikoh’s residence (the “library”) and was said to take a “walk” every evening with his 13 wives, riding as many elephants. But this was not the only reason for him being an extraordinary English officer: he belonged to a loyalist family of Boston which migrated to Canada after the Tea-Party. He then joined the English army in India, and was Resident at Delhi from 1803 to 1807. His mission was to make sure that under no circumstances would India go the way America did in 1776-1783, with or without French help.

Josiah Harlan was born in Newlin, Chester County, Pennsylvania, in 1799, the year Maharaja Ranjit Singh captured Lahore and founded the Sikh kingdom of Punjab. His eldest brother, Richard, was a physician, and young Josiah seems to have dabbled in medicine and surgery before he sailed on a merchant ship to Canton. Returning to America, he sailed out again—to Calcutta where the Bengal army, being short of surgeons during the Burmese War, enrolled him in July 1824. He served in Rangoon in 1825, then in Karnal with a regiment of Native infantry. He was on leave in Ludhiana in 1826 when he was informed that an order had been issued for the dismissal of temporary surgeons from the British army.

In 1827, Harlan asked and got permission from the British authorities to cross the Sutlej River, perhaps—as he himself declared later—to go by land to Saint-Petersburg. Proud of being “a free citizen of the United States”, a fact that was often sarcastically noted by British travelers and political officers in their writings, his plan was in fact to join Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s service. He was aware that the Maharaja had French officers serving him since 1822 and that, since the early days of Washington and La Fayette, cordial relations could be easily established between the French and the Americans. However, the Maharaja did not allow Harlan to enter his territories. So Harlan decided to go to Kabul through Bahawalpur, Kandahar and Ghazni in September 1827. He seems to have had at least three reasons for doing that.

The first was to study the natural history of these unknown areas, since Harlan had a keen eye for science and medicine. The second was to work as an agent for Shah Shuja-ul-Mulk, the exiled King of Afghanistan who resided with his retinue in Ludhiana, British territory, waiting to reconquer his throne. He hoped for the help of British subsidies, if not a British army. Harlan’s third motive was, perhaps, to try to recover the papers of William Moorcroft and George Trebeck who had been murdered near Mazar-e-Sharif in Northern Afghanistan while on an ill-concealed spying mission for the East India Company. For this last mission Harlan had no official appointment from the English authorities in India, but he had the secret help and financial backing of John Palmer, the “Prince of Merchants” of Calcutta. Palmer’s long arm extended from the Governor-General of India to Captain Wade, the assistant political agent at Ludhiana in charge of “Sikh” affairs. From 1826 onwards, the French generals in the service of Ranjit Singh and the Maharaja himself fell within his reach through the commerce that developed with members of the court.

We do not have much information on Harlan’s first sojourn in Afghanistan. Like the rare firangis traveling in that country at that time, he was welcomed by Jabbar Khan, one of the half-brothers of Dost Mohammed Khan, Emir of Kabul. Born of a Shia woman, Jabbar Khan was the head of the powerful Qizilbash Shia community in Afghanistan. Most of his hereditary estates were in Laghman, north of Jalalabad, on the way to Kafiristan. Jabbar Khan was a close friend of the French officers in the Lahore service, having received generals Court and Avitabile in Laghman in December 1826, when they were on their way from Persia to Lahore to join Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Whatever Harlan did in Kabul was most certainly known to General Allard in Lahore, and therefore also to Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

In early 1829 Harlan left Kabul and reached Lahore where he resided for a while, having enough money to live on without seeking any employment from the Maharaja. Ranjit Singh himself offered him the brigade of Oms, one of his French officers who had just died and whose elite regiments were stationed at Shandara, on the right (north) bank of the Ravi River. Harlan refused, saying that he was a medical practitioner and not a military man. He even informed Ranjit Singh that he planned to return to the United States. However, we know from British secret reports that Harlan had started practicing medicine in Lahore with considerable success. Realizing that he could not induce Harlan to join him as a military officer, the Maharaja offered him the position of Governor of Nurpur and Jasrota in December 1829.

These were two old Rajput principalities in the Himalayan foothills between Jammu and Kangra which Maharaja Ranjit Singh found difficult to integrate into his kingdom, especially since the Dogra brothers at Jammu were also quietly trying to extend their influence over them. Apparently Harlan lived there for some time though there is no information on how he managed this difficult appointment. But in March 1831 he was back in Lahore, recalled by the Maharaja because of the many complaints of influential people against him. In Lahore he took up residence with General Allard who afforded him protection during those difficult times.

There were apparently no serious faults on Harlan’s side since in May 1832 Ranjit Singh appointed him Governor of Gujrat (now a district in Pakistan) and invested him with a khilat (dress of honor) which was put on him by General Allard. He was even presented with an elephant and given the sanad conferring upon him the necessary authority for his government. Harlan had to sign a contract, which was deposited in the State Archives in Lahore, and swear on the Bible that he would faithfully serve the Maharaja. A few months later he was called back to Lahore because of the complaints of infuriated zamindars: this per se is not to be taken as a charge, since the Umdat-ut-Tawarikh has several examples of Ranjit Singh using his “French” officers to settle local affairs in which the zamindars complained, and the Maharaja burst into a rage against these oppressive and intolerant landholders. A very rare letter of Harlan—in his own hand—preserved today is addressed to General Allard dated October 1833, in which he stated that the complaint he had just made to the Sarkar (Ranjit Singh) was not intended against him (Allard), but against Ventura whose policies he could not stand. The fact that Ventura had jagirs (estates) in the district of Gujrat might be the cause of the out-burst, but we have no attested connection between these two facts. However, Harlan soon resumed his duty in Gujrat.

For whatever it is worth, British Resident of Punjab Henry Lawrence’s pseudo-testimony in his novel, Adventures of an Officer, says that the American Governor of Gujrat “is a man of considerable ability, great courage and enterprise.” That he was a jolly fellow is also attested by the Reverend Wolff who was received in his residence in Gujrat where he could hear him singing Yankee Doodle “with the true American snuffle.” Wolff described him as “a fine tall man, dressed in European clothing and smoking a hookah” who introduced himself as “a free citizen of the United States, from the city of Philadelphia.” During their discussions Harlan laughingly summarized his contract with the Maharaja as follows: “I [Ranjit Singh] will make you Governor of Gujrat. If you behave well, I will increase your salary. If not, I will cut your nose!” The observant Wolff concluded that –“the fact of his nose being entire proved that he had done well.”

During his early years in Ranjit Singh’s service Harlan kept in touch with Shah Shuja-ul-Mulk, the exiled king of Kabul who informed him of what was going on in Afghanistan. When in 1833 the Shah was preparing for one of his attempts to recover his throne, he was expecting Harlan to join him with 500 troops and a lakh of rupees. Harlan did not join the Shah during his disastrous expedition to Kandahar in 1834, most probably because of his duties in the Punjab kingdom. But the Kandahar affair served as a diversion: with Dost Mohammed Khan being engaged in Kandahar against Shah Shuja-ul-Mulk, Maharaja Ranjit Singh sent General Hari Singh Nalwa and General Court with their brigades who in a swift move annexed Peshawar and its province up to the Khyber Pass to the Punjab kingdom. Peshawar had been conquered and annexed to Afghanistan by Mahmud Ghaznavi in 1001-1005 AD. Ranjit Singh celebrated his own fait d’armes by ordering salvos of guns and illuminations in every city in the kingdom.

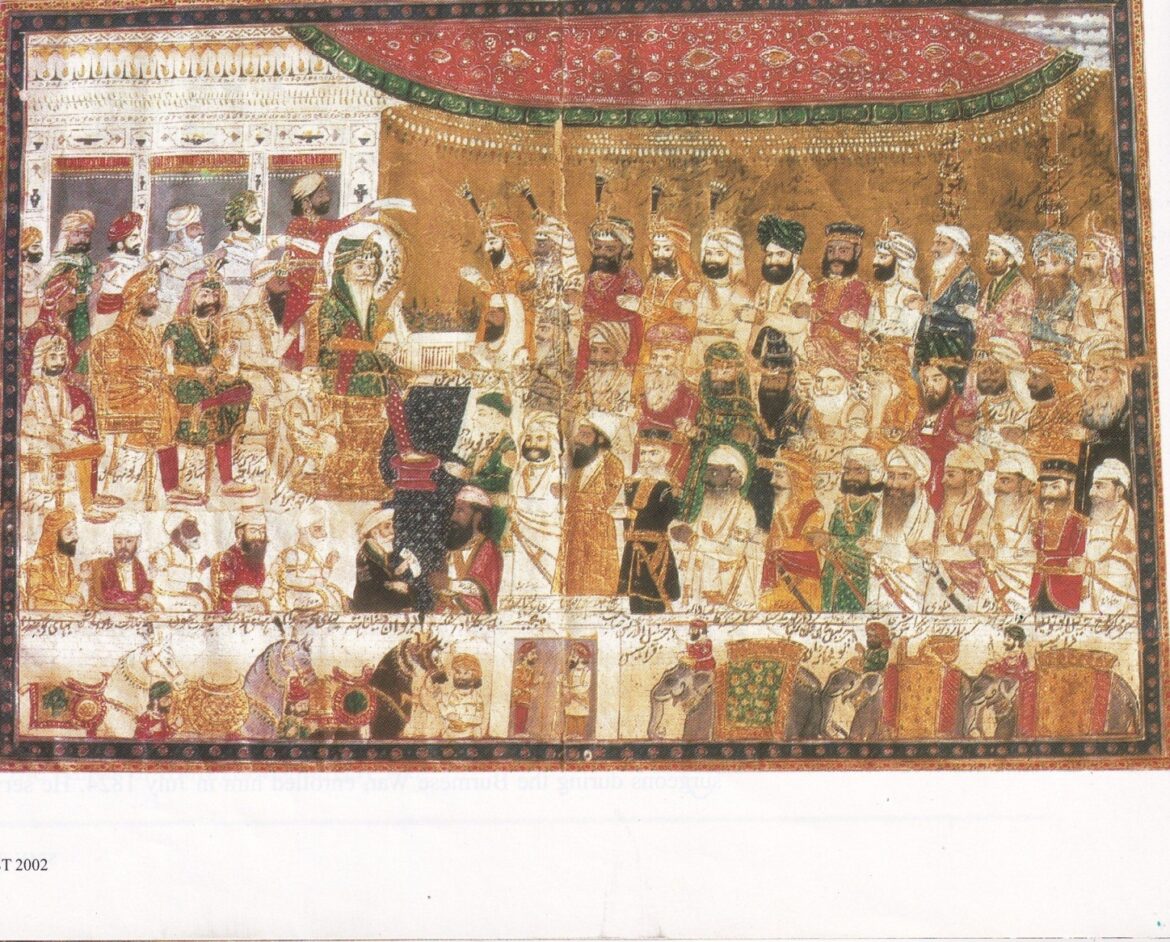

Dost Mohammed Khan protested against this annexation, and in 1835 he made his first attempt to recapture Peshawar through a jihad against the kafirs (the Sikhs) The jihad was joined by almost all the Muslim tribes of the Khyber Pass. British intelligence predicted that if Ranjit Singh was defeated, the whole Muslim population of Punjab would rise against the Sikhs, and the Maharaja would have the utmost difficulty in saving his kingdom. Well aware of this fact, Ranjit Singh sent his best troops, including his French brigades under the command of General Court, who began to encircle the entrance of the Khyber Pass in order to contain the tens of thousand jihadis or ghazis—the present-day mujahideen—who were pouring out of Afghanistan. General Court asked the Maharaja’s permission to carry out a night attack on the Afghans. Ranjit Singh’s strategy was to wait for more time, let the Afghans come out of the Khyber and then encircle and destroy them entirely. For that he needed a stratagem to keep Dost Mohammed Khan busy while he was maneuvering his units in an encircling move. The stratagem Ranjit Singh devised was to send an embassy to the Khan, and he selected two emissaries: Fakir Syed Aziz-ud-Din, his trusted minister of foreign affairs, and his American Governor, Josiah Harlan. That was on May 11, 1835.

We have several accounts on the way the negotiations took place in the Afghan darbar. There were tumultuous debates concerning the qualifications of the ambassadors themselves (“The Farenghis [are] like trees, full of leaves but producing no fruits.”), a gift of a copy of the Koran by Harlan to Dost Mohammed Khan and a fiery theological exchange between some Maulvis and Fakir Aziz-ud-Din on the Sharia, the Muslims and the kafirs. Amidst all this, Ranjit Singh was tightening the noose. Suddenly Dost Mohammed Khan was informed that the Afghan army was almost completely surrounded. It was a rout. Almost 60,000 men with horses and camels headed for the safety of the Khyber Pass. Dost Mohammed Khan, before jumping on his horse, ordered Fakir Aziz-ud-Din and Josiah Harlan to be delivered to his brother Sultan Mohammed Khan to be kept as hostages. Already bought by Harlan, Sultan Mohammed Khan sent them back safely under escort to the Punjab camp.

This apparent victory did not solve anything for Ranjit Singh, since the Afghan army had escaped unhurt before the Punjabi troops could complete their encircling move. The Maharaja was greatly incensed against Fakir Aziz-ud-Din. We might trace his growing discontent with Harlan also to that event, although several sources confirm his dismissal from the Punjab service in April 1836 was for another reason. Harlan was supposed to prepare a magical medicine for Ranjit Singh at the exorbitant price of one lakh rupees: a price to be paid in advance “as he did not trust the Maharaja”! Harlan was dismissed, paid his dues and escorted across the Sutlej River, to British territories. Wade reported his arrival in Ludhiana. Soon after he informed Calcutta of Harlan’s desire to enter the service of Dost Mohammed Khan at Kabul: “His declared intention is to bring down [to Peshawar] an army to avenge himself on his former master [Ranjit Singh] for the injuries he has received at his hands.”

Harlan retraced his journey to Kabul where he was warmly received (“like Themistocles”) by Dost Mohammed Khan and given the second regular infantry regiment to train, the first being trained and commanded by Rattray, a British subject. We have no details concerning the military training Harlan was able to impart to the troops under his command. We know that he was a member of the Kabul darbar although there were various levels of participation in such darbars. We also know he participated in the war launched by Dost Mohammed Khan to recapture Peshawar in 1837. The time was propitious for the Afghans, since Maharaja Ranjit Singh had called back to Lahore all his French Generals with their brigades in order to impress Lord Fane, commander-in-chief of the British army, who was in Lahore to attend the wedding of Prince Nau Nihal Singh in March. Lord Fane was impressed, but Jamrud narrowly escaped a storming by the sudden flow of ghazis who came out of the Khyber Pass. Peshawar was saved by the heroic deeds of General Hari Singh Nalwa, who was fatally wounded at Jamrud. But the Nalwa managed to fix the Afghans at the fortress of Jamrud, whose garrison sustained a terrible siege until they were relieved by the French brigades which made a forced march from Lahore to Peshawar in a couple of days. Maharaja Ranjit Singh then entrusted the civil and military command of Peshawar and its province to his three French generals, Allard, Court and Avitabile, who kept their brigades with them. There was no further attempt by the Afghans against Peshawar till 1849, after the British army defeated the Punjabis at the battle of Gujranwala. They were then repulsed by a British column into the Khyber Pass.

In his memoirs, Harlan laid claim to victory in the battle of Jamrud and the death of Hari Singh Nalwa. British historians, not very happy to acknowledge the efficiency of an American, usually prefered to praise Rattray and Campbell, two English deserters in the Afghan service at that time. What is sure is that after Jamrud, Harlan’s influence in Kabul increased. He has left us in his memoirs one of the best and most vivid descriptions of Amir Dost Mohammed Khan. In September 1838 Harlan was attached to his troops to the expedition against Mir Murad Beg of Qunduz. As he wrote in his memoirs, “1,400 cavalry; 1,100 effective infantry; and 100 artillery; total of fighting men, 2,600; camp followers, 1,000; grand total, 3,600 men; horses, 2,000; camels, 400; elephant, one,” which elephant was sent back from Bamiyan to Kabul because he could not sustain the cold anymore. Harlan and his men crossed the lofty passes of the Hindukush, stayed at Bamiyan on their way to Qunduz as well as on the way back. And as Harlan proudly wrote: “There upon the mountain heights [I] unfurled my country’s banner to the breeze, under a salute of twenty-six guns.” Harlan was back in Kabul in spring 1839, just in time to meet with the British advance troop of what was later known as the First Anglo-Afghan war. From the evidence that is available, his participation in the war is not clear at all. But in Kabul, Harlan met one Dr Kennedy who left an interesting portrait of him Despite the common prejudices of a British gentleman for an American “adventurer,” Dr. Kennedy made a number of sagacious and positive observations. We quote: “There was at this time at Kabul a certain ‘free and enlightened citizen of the greatest and most glorious country in the world [i.e. the USA…]’ in the person of a Dr. Harlan…. I met him one morning and was surprised to find a wonderful fund of local knowledge and great shrewdness in a tall manly figure with a large head and gaunt face, dressed in a light shining pea-jacket of green silk, maroon coloured small clothes, buff boots, a silver lace girdle fastened with a great silver buckle larger than a soldier’s breast plate, and on his head a white catskin foraging cap with a glittering gold band, precisely the figure that in my youth would have been the pride and joy of a Tyrolean Pandaen pipe band. Though he dressed like a mountebank, this gentleman was not a fool, and it will not be creditable to our Government if he is not provided for, as there is no law making it penal to have served against us, and the President and the Congress would have required an answer at our hand had we made it so.”

British authorities in India did provide for Dr. Harlan, for he was sent back to Ludhiana with the British forces returning to their barracks in September 1839 after the capture of Kabul. After a short stay there, he was transferred to Calcutta, and then sent back to the U.S.A. at the expenses of the East India Company. That was the end of his Indian adventures. He reached Philadelphia in August 1841 and a year later published A Memoir of India and Avghanistaun. This memoir was an objective—albeit terrible—analysis of the mechanisms and consequences of British colonialism in India: machiavellianism of the invaders, rapacity of the civil servants and the revenue collectors, a systematic looting of the country by a handful of colonizers, a general impoverishment of the population and a growing indebtedness of the peasants. According to him, the natives of India were no less slaves “than the enslaved Africans for whom the English affect the warmest sympathy.” These results were not the side effects, or the collateral damage, of a system whose implementation would be globally positive for the Indians: it was the perfection and willful accomplishment of a policy leaving to the peasants the smallest possible portion to survive, an analysis corroborated at the same period by French natural historian Victor Jacquemont and confirmed for the 1830s by several eminent specialists of British India today.

Moreover Harlan was the first to publish inside information concerning the way the British army bought its way to Kabul in 1839, describing the corruption on a great scale of the political agents from Kandahar to Ghazni to Kabul. He emphasized the miseries inflicted upon the populations in this war, and the political, spiritual and moral destabilization such a war was going to imprint on the tribes of Afghanistan. Harlan looks at these tribal populations sympathetically, more as a sociologist than as a historian, and the exactitude of his descriptions is striking for people who know Afghanistan. Some other aspects of his testimony concern the vain glory of the British military units during this campaign, victories which were purchased and not won, decorations raining on Kabul particularly, which did not recompense any military courage. He cites a Political Head of Mission, MacNaghten, who was nothing but a “Bombaste furioso,” and the magisterial incompetence of the political officers. When the revolt arose ultimately and the Afghan tribes started collecting to repulse the invaders, an indecisive army hesitated to move and ended up in a last stand on the hills of Gandamak, between Jalalabad and Kabul.

A Memoir of India and Avghanistaun was to be followed by A Narrative, which was never published in its entirety. Considering the magnitude and precision of Harlan’s accusations, which interpreter and adviser to the British government in Afghanistan Mohan Lal’s Life of the Amir Dost Mohammed Khan of Kabul confirmed with more detail a couple of years later, British authorities in Calcutta took all necessary steps to prevent the sale and distribution of the book.

Harlan spent the next 30 years of his life in the United States. He purchased and sold some estates around Philadelphia, married in 1849 and had a daughter. In the 1850s, when the American Government was considering the import of camels for military use in the deserts, Harlan supplied a lot of information coming from his experience in North-West India and Afghanistan. During the Civil War in 1861, he raised a regiment for the Union Army, called Harlan’s Light Cavalry, later known as the 11th Cavalry. He served as its colonel in the Army of the Potomac until he retired due to ill health in 1862. He then lived for a couple of years in Philadelphia, with his souvenirs, his papers and his collections. He also suggested to the government the import of vine-trees and other fruit-trees from Afghanistan into the U.S., and he even prepared an estimated budget—$10,000—for an expedition to be sent to collect the plants from Afghanistan.

Some years after the end of the Civil War, Harlan moved to San Francisco where he again practiced as a physician. He died there in October 1871. His wife returned to Philadelphia, where she died in 1884. Their daughter Sarah went to live in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and she had many papers, diaries, memoirs, drawings and correspondence of her father kept in several milk cans in her house. In 1929, a fire destroyed Sarah Harlan’s house, burning whatever was left of General Harlan’s adventures in Punjab and Afghanistan. Harlan had already published some extracts of his Narrative in 1842. Three completed chapters of this manuscript were given in 1908 to the Chester County Historical Society, from where they were published by Frank E. Ross in 1939 under the title Central Asia. Personal Narrative of General Josiah Harlan (1823-1841). That is all we have now of what Josiah Harlan wanted to tell us about his extraordinary life in Punjab and Afghanistan.

Jean-Marie Lafont